by L.M. Browning

Featuring field photos by the author.

This article is featured in the Autumn 2015 issue of The Wayfarer (Vol 4 Issue 2)

Visit our bookstore to purchase an e-edition or print edition. Go to the Store»

May 4, 2015 | Napatree Point, Rhode Island

The first true warmth of spring arrives and my friend Alex and I decide to drive down to Watch Hill, Rhode Island and walk Napatree Point, a tucked away strip of shore in southern Rhode Island.

It is said that the name “Napatree” is derived from Nape (Neck) of Trees. Up until the Great September Gale of 1815, the land was densely wooded. The trees were stripped away by the storm, the strength of which would rate a category 3 on the modern Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale.

My fond memories of Napatree go back some 30 years to when my mother first brought me to walk the beach as a child. After strolling along the shore, we would walk into the nearby town of Watch Hill (a small endearing beach village with a Hamptons-esque quality) where she would give me a couple dollars to ride the carousel, which lies at the heart of the village.

The “Flying Horses Carousel” as it is called, is composed of 20 horses, suspended by chains underneath a multicolored canopy. When the carousel spins, centrifugal force pulls the horses outward, thus it earned its name the “Flying Horses”. The jolly tune that plays while the horses fly emanates from a hand-crank organ found at the center of the main pillar. In 1987, the carousel was declared a National Historical Landmark. It has run in the village of Watch Hill since 1879 when a traveling carnival was forced to leave it behind.

I still remember gripping the chains as I sat on the horses, the leather strap holding me to the hard saddle straining against my waist as I reached for the brass ring.

On this particular spring afternoon, Alex and I pass through Watch Hill on our way to Napatree. I see the carousel spinning like a dervish, the chimes and pipes of the organ music are still just as enchanting as when I first heard them. I pause for a moment at the rail and watch the jubilant colors turn, the laughter of the children a joyful counterpoint to music. As we stand there, I wonder how I was ever small enough to fit on one of the ponies, and, with a scent of popcorn, candy, and ice cream in the air, we press on to the point.

This day hike was to be the first since the fall. In the summer of 2014 I suffered a Trimalleolar fracture and dislocation. (In layman’s terms: I dislocated my ankle and broke it in three places. More damaging than the bone breaks, was the extensive soft tissue damage done by the dislocation). All of this resulting in what is termed an “unstable ankle fracture” that can only be mended through surgical intervention.

If this injury had happened 100 years sooner, I’d never walked properly again and most certainly would have re-broken it several times within my life, but, in this day and age, titanium heals all. Run enough screws, plates, and wire through the bone and even the most broken of joints can be held together.

Confined to my bed for six weeks after the reconstructive surgery, I went from hiking through the woodlands of New England to shuffling along on a brand new walker—fully outfitted with four spiffy tennis balls. Six months recovery, three months of physical therapy, four different casts, and two braces later, I find myself moving along better each day.

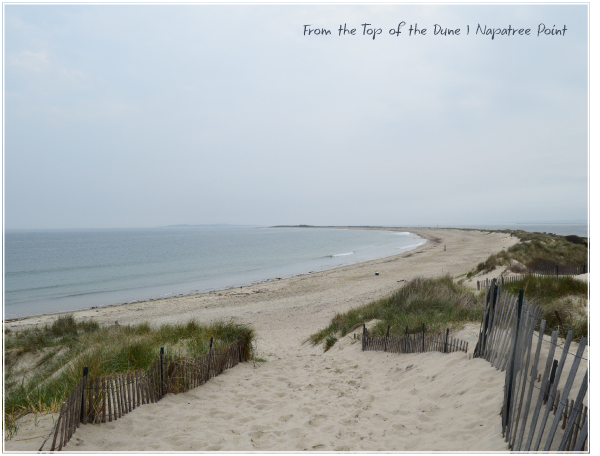

Napatree would be the test of the still-healing joint. I exchanged the walnut cane for a metal trek pole, strung my shoes together, threw them over my shoulder, and set out towards the beach. The first hurdle would be the rather tall sand dune that one must climb to reach the sheltered shore. This posed a problem for my ankle, which still had difficulty reaching certain angles.

“The tall sand is particularly difficult,” I comment to Alex as we start the climb, “you don’t realize the dozens of corrections the muscles and ligaments in your ankle makes to support you in the uneven sand until you can feel every single tendon firing and straining.”

My foot could strain to reach a 90 degree position, but pushing off from that angle to take the next step was terribly uncomfortable. Determined as I was to see the ocean, I shuffled up the dune and gently walked down the other side, descending to the shore, a long rock jetty at my left and the sandy peninsula of the shore stretching out, making my way down to the compacted sand along the waterline.

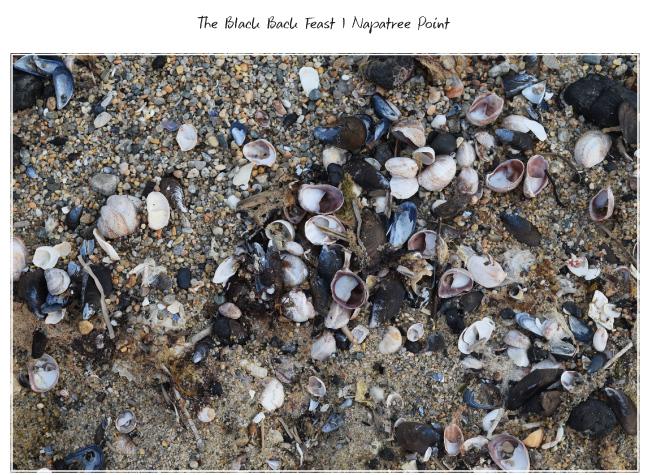

We started down the shore. Pushed by the high gales, the waves drove hard against the shore. Black Back gulls hovered like feathered dirigibles overhead, perching expertly on the turbulent wind. Only moments before, they’d had their morning feast. Opened mussels and scooped out spider crab heads were scattered along the sand. Every now and again we came upon a lone blue mussel sitting upon the sand that had managed to survive the feeding frenzy. I picked up each one, aware of the little frightened creature closed tight within, and tossed it into the salty swells.

All along the rock jetty erected to shelter Watch Hill, cluster mussels grew as thick as dragon scales. Somehow, I’d never noticed the colony until now. I followed the wall of rocks into the cold May waters of the North Atlantic. A species of sea lettuce clung in-between the shells, the translucent topical green interspersed among the black and blue mussels. Something about the densely huddled mussels made me think about community and the joy of growing together.

Soothed by the surf and fresh wind, I made the decision (perhaps foolishly) to walk the full length of the beach, walk all the way do to the fort.

In addition to the present-day nature conservancy, Napatree Point was also home to Fort Mansfield. In 1883, a joint Army-Navy Board that would later be known as the “Endicott Board” issued a report exposing the defenselessness of the United States’ coast. Fort Mansfield was but one of the 53 shoreline forts constructed along the East coast during the Endicott Period (1890-1910) in an effort to secure coastal towns and harbors from attack. 81 installations were constructed in total. In 1898, the government purchased 60 acres along Napatree Point and construction for Fort Mansfield began. The facility was completed in 1902 and acted as a small, single company, outpost. In July 1907 during routine war games a fatal flaw was discovered in outpost, which led to the deactivation of the fort in 1909. Ten years later, the fort was demolished; only 3 concrete gun emplacements were left behind. Remnants of two still remain, while one has become a victim to rising tides and sea erosion, which has pushed the beach back some 200 feet since 1898.

Almost immediately after deciding to walk down to the fort, the smooth path grew difficult. Mounds of dense stone littered the shore. The gravel, while smoothed by the tumbling tide, was rough against by bare feet that had been softened over my months of inactivity. A fierce tide must have deposited gritty sand up along the shore. A strip of red kelp pushed up by the waves drew a line from the dunes down along the length of the beach off into the distance. It had dried in the sun and now waited to be folded back into the sea during the next high tide. Intermingled within the leaves, were a confetti of crustaceans and mollusks: tiny sea urchins, clams, mussels, and sea slippers stacked one on top of the next (some alive, some dead).

Alex and I always hike altruistically, routinely picking up clumps of still-closed blue mussels and stacked sea slipper stranded high on the beach and tossing them back into the water. Some creatures were sadly beyond aid. Dismembered legs and heads of spider crabs, shrimp, Atlantic blue crabs, rock crabs, lobsters, and horseshoe crabs trailed along the shore. The brown sand dotted now and again by the ripped sacks of the devil purses—the eggs sacks of sharks, skates, and chimaeras (most likely skates in this case).

Two thirds of the way down the shore, we spotted a lone survivor. I’d found a small graveyard of horseshoe crab skeletons. The waters around Napatree are a mating ground for pre-historic creatures. (The earliest evidence of the species dating back some 450 million years, to the Ordovician period). I hovered over one of the dead. It was intact. It lay on its back legs and tail stiffly pointed in the air. “Poor crab.” I commented empathetically. Alex came closer to see what exactly I’d found when suddenly the crab’s legs started flailing rapidly in the air. I lean in closer to see what was going on, noticing that the crab had been hogtied—tail in all—by a long piece of red kelp. Black back gulls started circling overhead, likewise drawn by the crab’s movement. Rushing to the crab’s aid, Andy carried him (judging by the small size, it was most likely male) back down to the surf where he floated down into the obscured depths of the ocean floor. We walked on.

The talk of the insignificant stresses of the business day fell silent. Both of us basking in the knowledge that something of value had been accomplished today: we’d saved a life. And not just one life actually but dozens. You see, while few know it, I am the patron of sea slippers. While walking Napatree, every few yards I inevitably find a stack of the tiny creatures drying out far up on the shore that I must stop rescue. Something about the smallness of their little community and their fragility compels me to help them.

Sea slippers are prominent along the shores of Napatree so our hike is more a rescue mission than a outing. A type of sea snail, sea slippers are also known as common Atlantic slipper snails, quarterdeck shells, or Atlantic Slipper Limpets. Often sea slippers will cling on to rocks, pilings or even horseshoe crabs but most often they live in stacks. The oldest female being the base of the pile while the younger small males are on top, the species is a sequential hermaphrodite. If the female should die, the largest male in the stack will become female.

As we walked on and I ferry the stranded creatures back to the sea, I thought back to the sometimes-absurd lengths I’d gone to over the years to help animals; whether it was when I was eight and I cared for a lone killdeer chick after its mother died, to the time when I was learning how to drive on the dirt roads of rural upstate New York when I suddenly swerved inexplicably.

“What happened?” the instructor exclaimed at a loss.

“Woolly bear” I replied meekly, “there was a woolly bear in the road. It wasn’t like there was oncoming traffic.” I went on, trying to expel the dumbfounded look creasing his face. We came to a stop along the utterly deserted country road.

He quickly looked out the back window , “How did you even see it?”

“I was looking.” I replied, not knowing what else to say.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve felt an overflowing empathy for wildlife. I feel more connected to the encroached upon animal than I do that of Western society. The kinship I feel for the wild has been there within me since I was a child. I spent the summers of my childhood knee-deep in ponds meeting bullfrogs and sun turtles, and my springs and autumns exploring the woodlands around our home. I can’t pinpoint exactly what, but something about the exchange when I encounter an animal in the wild is revelatory to me. After each encounter, I am left feeling varying depths of awe, and in this awe find peace and belonging.

Nature is a mystery of immeasurable complexity that cannot and need not be fully understood. The sense of awe we feel when beholding the wild is rooted in our appreciation of the infinite intricacy interweaving all things together, and the unspoken surrender of our need to comprehend it all. Awe arises as the ego recedes. It is an instant wherein we recognize the magnitude of elements at work, and are grateful for having even the smallest of roles in the drama of existence playing out within the universe.

Looking up from my ponderings, I see Alex climbing through a labyrinth of rocks scattered within the waves. We’d made it to the fort. As Andy explored the surround, I sat on a cluster of rocks for a time. The hollow iron bell of a buoy clanged in time with the swells in the distance. Stepping from rock to rock, I moved deeper out into the water, finally coming to rest on a larger boulder only half submerged in the incoming tide. Looking down at my feet in the cold water I witnessed a plethora of life. Blue mussels, slipper shells, and a fleet of sea snails no bigger than pebbles swarmed in the pooling breakwater. A tiny spider crab reached a claw out from under a nearby rock. A dead one lay only a few inches away. Hopefully not a companion.

A garden of barnacles covered the side of each rock. Some were so large the pearl petals of the calcareous plates were clearly visible.

I glanced back at the mile and a half of beach we’d covered. As my foot ached, a single thought occurred to me: We still have to walk back.

A flood of worry entered me, but I pushed the worry from my mind. That journey would be confronted later. The moment, I reminded myself, wasn’t for dwelling on the difficulties that lay ahead, but appreciating the beauty already present.

Isak Dinesen famously writes, “The cure for anything is salt water: sweat, tears or the sea.” As the snowy spray from the breaking waves kisses my face, this truth resounds. Setting out this morning, my mind was heavy from work and worry, my body weary from illness and injury. Yet the sea, with its consoling balm, had washed that strain away, even if only for a time. In the distance, I heard scream a pair of ospreys. A flock of four oystercatchers chattered loudly as they beat their wings across the horizon. Piping Plovers scuttled about almost indistinguishable from the dried grass speckling the dunes. The bell sounded. My bare scarred leg soaked in the cold salty Atlantic. The waves crash upon the ruined battlements of the fort. The wind suddenly shifted, leaving my mind to soak in the stillness.

L.M. Browning grew up in a small fishing village in Connecticut. A longtime student of religion, nature, art, and philosophy these themes permeate her work. Browning is the author of numerous award-winning titles. In 2010, she debuted as a writer with a three-title contemplative poetry series: Ruminations at Twilight, Oak Wise, and The Barren Plain. These three books went on to garner several accolades including a total of 3 pushcart-prize nominations and the Nautilus Gold Medal for Poetry in 2013. She followed this success with her first novel, The Nameless Man. In 2013 Her title, Fleeting Moments of Fierce Clarity: Journal of a New England Poet, was named a finalist in the Next Generation Indie Book Awards (Best Regional Non-fiction) and was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Balancing her passion for writing with her love of education and publishing, Browning is a graduate of the University of London and a Fellow with the League of Conservationist Writers. She is partner at Hiraeth Press; Co-Founder of Written River as well as Founder and Editor-in-Chief of The Wayfarer. In 2011, Browning opened Homebound Publications—a rising independent publishing house. She is currently working on her B.A. at Harvard University’s Extension School in Cambridge, Massachusetts. To learn more go to www.lmbrowning.com

L.M. Browning grew up in a small fishing village in Connecticut. A longtime student of religion, nature, art, and philosophy these themes permeate her work. Browning is the author of numerous award-winning titles. In 2010, she debuted as a writer with a three-title contemplative poetry series: Ruminations at Twilight, Oak Wise, and The Barren Plain. These three books went on to garner several accolades including a total of 3 pushcart-prize nominations and the Nautilus Gold Medal for Poetry in 2013. She followed this success with her first novel, The Nameless Man. In 2013 Her title, Fleeting Moments of Fierce Clarity: Journal of a New England Poet, was named a finalist in the Next Generation Indie Book Awards (Best Regional Non-fiction) and was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Balancing her passion for writing with her love of education and publishing, Browning is a graduate of the University of London and a Fellow with the League of Conservationist Writers. She is partner at Hiraeth Press; Co-Founder of Written River as well as Founder and Editor-in-Chief of The Wayfarer. In 2011, Browning opened Homebound Publications—a rising independent publishing house. She is currently working on her B.A. at Harvard University’s Extension School in Cambridge, Massachusetts. To learn more go to www.lmbrowning.com