Featured in Vol 2 Issue 1

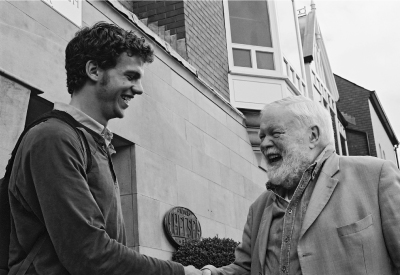

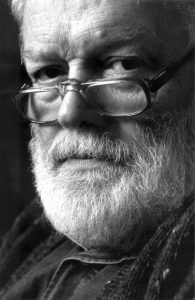

Photo of Author and Michael Longley © Scott Rodd | Photo Header: War Poets Association website. © Patrick Redmond

When I first saw Michael Longley, I knew immediately it was him. The bright white beard was telltale, but it was his manner that revealed the character of the man. I watched him from the other side of the street, slowly making his way toward me, with a green reusable shopping bag and a tall red umbrella under his arm. He seemed to be lost in a reverie, yet keenly attentive to the particularities of the world around him. As he shuffled along in his high-waisted trousers, off-balanced by the awkwardness of the umbrella, he would look up, notice some flower or object in a shop window, and then, with a funny little bob of his head, pay his respects and trundle along.

He saw me as he reached the curb, and his face crinkled up in a curious combination of a smile and a squint. “Are you Emm-mett?” he asked, enunciating the syllables of my name carefully. His eyes were beady, birdlike. He winked often and seemingly unconsciously, giving the impression of a keen but friendly intelligence behind his gentle demeanor. I told him I was, and shook his extended hand, noticing how small, scabby, and somewhat tired it was. He stooped over his umbrella like a cane, back hunched, somewhat smaller than I’d imagined him. Longley’s physical was a palpable reminder to me that the poet had aged even as his poetry remains young. He is 72 now, and in a month he will be 73. He said he is “perhaps too much in love with his granddaughter,” but he indignantly protested one critic’s suggestion that his recent poems dedicated to his grandsons are “sentimental.”

Longley hadn’t come empty-handed (even after setting down his umbrella and reusable bag). “If you have one of these already, give this to a friend,” he said. It was a limited print copy of his early translations, entitled Wavelengths. “It’s more Latin than Greek,” he apologized. The thin volume was beautifully bound and stenciled with wood engravings done by one of Longley’s friends. I was speechless. What inspired such generosity towards me in this gentle, marvelous man? I asked him how he could be so kind to me when there were tons of students who’d love to sit down to chat with him. “Oh, really?” he said quietly, “are there?….I guess I wouldn’t really have a sense for that kind of thing. I thought I was rather anonymous.” His humility faded into a more personal note: “You know, the reason I decided to talk…to have lunch with you,” he said warmly, “is because I liked your letters. I liked the way you wrote to me.”

Longley was referring to the miniature letter campaign I’d launched to secure our meeting. After a number of exchanges with his US publisher at Wake Forest, I’d succeeded in obtaining an e-mail address. I knew this was my chance to convince Longley to meet me. I told him of my interest in him, and my senior thesis, describing myself as “a fellow Homer-haunted soul, a student and a great admirer of yours.” I thought that would grab his attention, but I couldn’t resist adding one final hook: “In a different sense than you may have originally meant the words, I’ll mention a quote of yours which has especially inspired me: ‘If I knew where poems come from, I’d go there.’ For me, the imperative within that statement was clear, and so I’ve come to Ireland to find the poetry I love.” A few hours later, Longley responded with a brief e-mail inviting me to “have lunch or something like that” in Belfast. “It pleases me a great deal that you enjoy my versions,” he wrote at the bottom.

He was lonely, in a way, I realized as we talked over lunch. Not that he didn’t have friends- his correspondences with Mahon and Heaney are legendary, and he struck up conversation easily with the other diners. But someone to talk Homer with—I think he was almost as excited as I was for that.

“So you love Homer, do you?” Longley asked me. “Yes,” I said, smiling. “I do, too” he said, and that seemed to seal our initial liking for one another into a more concrete alliance. The first thing Longley wanted to know was whether I wrote poetry. I laughed and told him I only write the occasional romantic poem. He grinned knowingly. “Work, don’t they?” he applauded. “Why do you think the girls believe all that?” I laughed. “Because it’s beautiful,” I said. “Oh,” he said. “Yes, it can be.”

“So what have you been reading now,” he wanted to know. “Most scholarship I find a little boring,” he whispered, leaning in conspiratorially. “You say that like it’s a secret,” I said. He leaned back his head and guffawed. “Oh, that’s a good one,” he said. “That’s very good.”

I asked Longley about his time as a classics student at Trinity. He spoke fondly of his old teacher, Stanford, who was a “beautiful man, within and without.” Greek class with Stanford, however, could be very “stiff” and “old school.” As an undergraduate, Longley confessed to being rather lackadaisical about attending Stanford’s mandatory lectures. Once, after he had missed several weeks in a row, Stanford confronted him rather sternly: “Where were you at the lecture yesterday, Longley?” Longley chuckled as he recounted his response: “I overslept, Prof. Stanford, and couldn’t make it over in time.” Stanford: “The lecture was at 11…Where do you live, Longley?” Turns out Longley slept in a dorm hall on campus, five minutes from the lecture. Stanford instructed Longley to see him at Stanford’s office early in the next week. As Longley remembers, he spent the weekend dreading the meeting, expecting to be set back a year in his studies for failing to attend the lecture. That weekend, however, one of his poems was published in Icarus, Trinity’s poetry journal. Next week he came in to Stanford’s office, expecting the worst. Stanford’s demeanor was severe. He dressed Longley down sternly, explaining that attendance was mandatory and that Longley’s truancy was grounds for failing him. “And do you expect me to let you get away with that, just because you’re a poet?” he concluded. “Certainly not, sir,” Longley returned. “Well, I’m going to,” said the inveterate Stanford, “because I like your poems.”

I asked Longley about his time as a classics student at Trinity. He spoke fondly of his old teacher, Stanford, who was a “beautiful man, within and without.” Greek class with Stanford, however, could be very “stiff” and “old school.” As an undergraduate, Longley confessed to being rather lackadaisical about attending Stanford’s mandatory lectures. Once, after he had missed several weeks in a row, Stanford confronted him rather sternly: “Where were you at the lecture yesterday, Longley?” Longley chuckled as he recounted his response: “I overslept, Prof. Stanford, and couldn’t make it over in time.” Stanford: “The lecture was at 11…Where do you live, Longley?” Turns out Longley slept in a dorm hall on campus, five minutes from the lecture. Stanford instructed Longley to see him at Stanford’s office early in the next week. As Longley remembers, he spent the weekend dreading the meeting, expecting to be set back a year in his studies for failing to attend the lecture. That weekend, however, one of his poems was published in Icarus, Trinity’s poetry journal. Next week he came in to Stanford’s office, expecting the worst. Stanford’s demeanor was severe. He dressed Longley down sternly, explaining that attendance was mandatory and that Longley’s truancy was grounds for failing him. “And do you expect me to let you get away with that, just because you’re a poet?” he concluded. “Certainly not, sir,” Longley returned. “Well, I’m going to,” said the inveterate Stanford, “because I like your poems.”

Longley told another Stanford story, this one with a trace of pride. The class had been reading Aristotle’s Poetics, and Longley had been (once again) lax in completing his reading. Called upon in class to say something insightful about poetry and prose, he burst out, “Well sir, if prose is a river, poetry’s a fountain.” Years later, Longley told me, he returned to Trinity for a class reunion and Stanford approached him from across the room, “If I could do it all over again,” said the now-elderly Stanford, “I’d be a poet rather than a scholar.” Longley gave me a long look. “I wish I’d attended more of his lectures,” he said.

I wanted to ask Longley about Homer more directly, so I took the next chance to ask him about his return to the classics after nearly three decades. From 1969 until 1991, Homer had almost completely disappeared from Longley’s work. Then, in Gorse Fires, he launched a set of seven Homeric poems. I asked Longley about the two explanations he has given in the past for this sudden emergence. One was that events in his own life led him to seek resonance in Homer, who “let me write belated lamentation for my mother and father.” Another was that Homer empowered him to comment obliquely on political violence in Ireland. So I asked him if he thought these two themes were only coincidentally related, or if there was a connection that brought both of them out in his Homeric versions. “I hate those binaries,” he said. “Critics love them, but they’re always too simple.”

“Poetry is like a flick of the wrist,” Longley told me before lunch was over, making the motion with his hand. “You have to be insouciant. It’s like anything else. Have you ever made a group of people laugh? Writing a good poem is like that. It’s better than food, than drink, than sex even. And that’s saying something!” Talking about the poets he’s read and studied over the course of his life, Longley said offhand, “People sort of blast your soul sometimes; they don’t know they’re doing it.” Did he know what he was doing?

Suddenly tired, he stood to go, and gathered his things about him. Outside, he opened his umbrella with the delight of a child. “I got it in France,” he said. “It’s a poppy, see?” He was already drifting back into his dream world of flowers, birds, and snatches of ancient poetry. “We will be in touch,” he said. “It was a great pleasure to talk with you.” I watched him as he shuffled off, his sleepy movements like dance steps to music only the dancer could hear.

—Emmett Gilles

June 29, 2012 – Belfast, Northern Ireland

The author, Emmett Gilles is a senior Classics and Comparative Literature major at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. For his senior thesis on “Homer in the Poetry of Michael Longley”, he traveled to Ireland this summer to interview Michael Longley.

~

Michael Longley is a contemporary poet from Belfast, Northern Ireland. Educated in the Classics at Trinity College Dublin, where he published his first poems in the journal Icarus, Longley returned to Belfast in the sixties to continue writing and publishing poetry, even as sectarian violence drove poets like Seamus Heaney and Derek Mahon out of Northern Ireland. Longley’s later collections return to Homer in lyrical, freestanding versions that comment obliquely on personal grief and political violence in the poet’s community. Most famous among these is the sonnet “Ceasefire,” which reflects upon the provisional IRA ceasefire of 1994 through the reconciliation scene between Priam and Achilles in Book XXIV of the Iliad.