Leslie: In your debut poetry collection, Water, Rocks and Trees, you wade into the wild with humble reverence for what natural revelations the wild yields. In your photography, you seem to do the same only with a lens instead of a pen. How do you choose which moments to capture?

James: I often walk the dusty canyon road that runs along the South Platte river with my fly rod in my hand and my camera clipped to the shoulder strap of my fishing vest. I find myself reaching for the camera as I see something, something that makes me stop and take a deeper or longer look. This is reflexive, probably akin to the ancient practice of hunting and gathering. This might be the moment you’re asking about, the moment most of us associate with doing outdoor or wildlife photography. It could be anything from a bird to a flower to a scene of grandeur or beauty, like water tumbling over rocks the size of my truck or a newly hatched mayfly lit by the sun on a willow leaf. These are the common assumptions we can make about photography, and for good reason.

There’s more to it than that. I have become acquainted with a mutuality to the exchange between myself and what I am seeing. Now that I have spent a few years engaged in this endeavor I’ve learned I’m not doing much of the choosing. It’s more like the “natural revelations” that you speak of are summoning me to convey something. I’m becoming a mere refractor, a light-bender, a kind of consciousness for the camera. I’m using the camera as a modern tool to highlight a small part of the bigger story that is asking to be told.

Leslie: Tell us a little more about your home in Colorado, which seems to be the epicenter of where most of your photos take place.

James: I live on 16 acres of prairie land at the foot of the Rocky Mountains. When the early settlers arrived in this area, this parcel was made part of an alfalfa farm and then, in 1958, became platted as the first 3 lots of a rural residential subdivision. Most importantly, it hosts the convergence of two creeks that run year around and flow down through the Fountain Creek Watershed in southern Colorado eventually reaching the Arkansas river, the Mississippi river and on to the Gulf of Mexico. The water makes for a vital junction point for wild animals ranging down from the National Forest or along many miles of the riparian zone. The portion of land along the creek is a natural migratory channel for waterfowl and home to innumerable species of seasonal and permanent resident birds. The broader ecosystem here remains robust with only slight imbalances that have occurred. The prairie dog population is growing unchecked because the local fox population was killed off by an outbreak of parvovirus. Only this last winter did I see a return of the fox after 4 years being absent.

I walk along the creek almost daily. There is a remarkable mutability to the land that sits along the water. A time-lapse video over 10 years would reveal dramatic changes in the shape of the land, it’s vegetation and its wildlife. When the beaver move in, and I am hoping for a new cycle of dam building in the next year or two, I will walk beside widening ponds that are 4 to 5 feet deep instead of a narrow creek that is only 6 to 12 inches deep. The ponds are inviting to ducks and geese, herons and cormorants. I see deer every day. I have watched black-tailed weasel poke around in the rock piles and invade the homes of pocket gophers. I have seen raccoon and smelled the skunk. The cliff swallows return from South America each summer and sometimes attempt to build their muddy nests beneath the eaves. There are a multitude of ground vermin, moles and voles. One dark night, I listened with an intense aversion to the awful sound of a deer being killed by a mountain lion perhaps only 200 feet off the back deck. The next morning, I found the remains protruding upward through a thin veneer of ice on the creek.

On my walks, I try to imagine the land as it might have sat untouched a thousand years ago. I wonder how pure the water was, how serene the tall grasses were with little to speak of in terms of the noxious species of thistle, knapweed, and spurge. Was there a settlement of native people here or nearby? These older spirits of soil that has not been violated or water that has not been tainted will not return during my lifetime. But, I can still feel them. And the flora and fauna that remain hosted here are those from which I have borrowed my time to occupy this space and lend it my protection.

Leslie: Tell us a little about your photographic ritual? Do you get up every morning at dawn and go out to shoot or do you simply go about your day, camera in-hand?

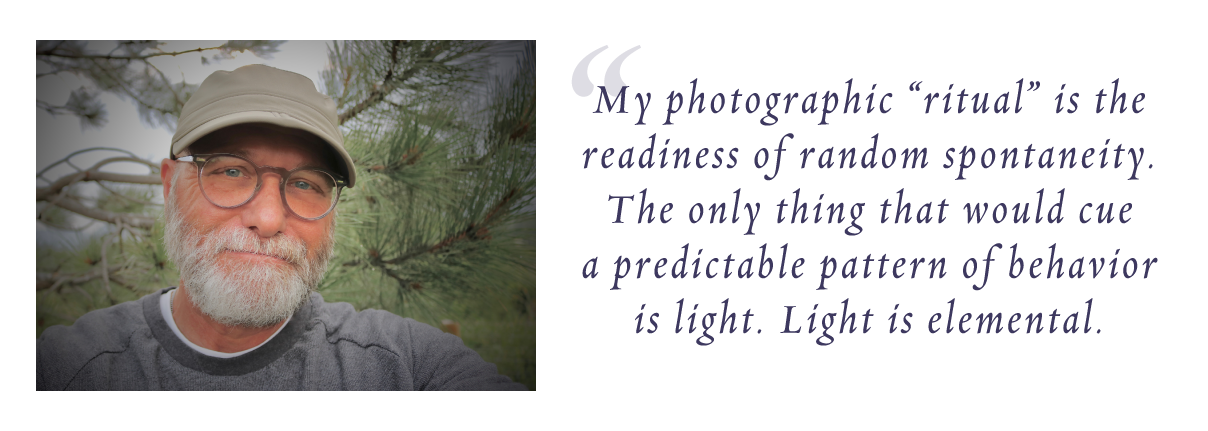

James: My photographic “ritual” is the readiness of random spontaneity. The only thing that would cue a predictable pattern of behavior is light. Light is elemental. So yes, morning and evening are often the best conditions under which to see. Also, because I care for domestic dogs as part of our family business, I’m rarely without my camera during the morning migration exercise and many of my better images of birds and wildlife have been taken while I walked in the dog meadow. During the afternoon, when I’m free, sometimes I’ll drive the half mile to the trails of the National Forest and walk in the shade of the Ponderosas.

When I leave the house, usually for the river, I have my camera within arm’s reach in the truck and then, as I said, clipped to my vest when I’m in the water. When I’m in the backcountry, I have my camera on the trail, ready to access almost instantly. I experience photography like I do my poetry. They usually happen as I’m doing something else. My job is to remove the limiting conditions that exist in my heart and mind or in the environment that would cause me to miss the moment when the natural realm wants to express itself.

If poetry and photography are my avocations, in other words, if they happen as an outgrowth of my daily routine of plain living or working or adventuring, then there can be no ritual about either one, which to me sounds lethal to the spirit of conveyance anyway. I want to be close to my notebook and pen and close to my camera. And, I want to be open, looking up and out, asking what is being said, what is being shown. Beneath the spontaneity is a readiness, a willingness to bear witness. I never know when this might happen, but it is a faith-worthy process.

Leslie: Do you consider your photography a study of the land? In what context do you view your work?

James: I believe that photography can be a study of the land for its own sake. I have been steeped in intrigue by the likes of John Muir, Aldo Leopold and Wendell Berry my entire adult life. Hell, my beloved Leonberger dog was named Ansel. However, I have a deeper personal interest in modern eco-socio-psychology and the mystery of the fusion of nature and human soulfulness as the basis of an organic faith. I used to try to find and even formulate a theoretical orientation to the nature-human-art dynamic that is having an impact on the evolution of human consciousness. After a period of research and study I grew to simply accept that I could relinquish the feverish intellectualizing and simply move out into the world, capture those fractals of revelation in a digitalized format or through the written word and then share it in the free and open cyber network that is ours today.

Social media, the most dubious and clamorous milieu there could ever be still provides each of us an opportunity if we are thinking about it. The question is: what to put out there? Apparently, most people do not have a conscious philosophical or ethical position on the content of their Facebook page. I’m working on it. I remember the days when I entered the fray on politics during election cycles or distracted myself in tedious or trivial discussions on religion or sports. As important as these things might be, at some point I withdrew from the contest and simply started sharing my photographs and my poems and began enjoying those of others. I decided that I was going to impose images of the natural realm into this most contrived space. That’s when I began to connect with people outside the confines of my immediate cultural cloister and away from the white noise. What I received back was the saliency of not feeling so alone, in learning “there are others”.

This is the context of my photography and my poetry: a deepening belongingness to the earth and a resonance with the kindred. My underlying assumption is that immersion in the primal domain is vital to the process of moving through our anxious reactivity to the forms of modern culture toward a more natural creative integrity we were born to possess. Personally, this begins with an interesting thing that happens inside me when I hang my camera around my neck or post a new poem on my blog. First, I immediately begin seeing the environment more keenly, as if it knows I’m there to represent and it heightens itself to my attention. The same is true with the written word. I can read a poem that I’ve written from the slightly nuanced perspective of another person as if observation alone truly does change the thing being observed. The poem becomes something new to me, and often gets revised based on that experience of imagination. Secondly, I am immediately enjoined with my friends, my viewers or readers, each as individuals, not en masse. It’s a meaningful connection with other unique human beings.

Leslie: Your photography reflects the tone of your poetry as though it is a poetic manifestation in and of itself. Is this a conscious choice or is it just organic?

James: My photography and poetry rise from the same source. Having little formal education in either area leads me to operate from core instinct. It doesn’t surprise me that the two mediums are recognizable littermates. I feel it that way. As I have learned what “folk art” is, colloquial and naïve, I think there is some of that quality in my work. I like to think of it as a child-like energy, a faith that emerges from a sense of wonder, sehnsucht, a longing for joy and justice that gets passed along through the work.

Leslie: Among your vast portfolio of images, which is your favorite moment captured and why?

James: Recently, I caught sight of a scrub jay going about its business. As I was processing the images I came upon one particular frame that showed the bird entranced with some form of prey or sustenance in the tall grass below. I was drawn in by the utter singularity of purpose or drive in the bird, the complete dedication to being what it is, and its apparent lack of interest in me while it hunted. There is no magnificence here. There is only the motion of moving forward, of being and doing as if each were the same thing, as though there is nothing else outside this moment. And it is refreshingly void of human contrivance. I have witnessed this kind of faith in many creatures when I have allowed myself to stop anthropomorphizing, to stop imposing my own image on the created order. This image causes me to contemplate and access my own creatureliness. And yet, it also inspires a sense of teleology, a prompting that says “become this” or “consider living this way”. I don’t always capture that deeper view of incarnation, but in this case, I think I came close.

Leslie: What’s next? What are you currently working on?

James: I will continue sharing my first collection of poetry, Water, Rocks and Trees. Also, I am completing my second book entitled The Expanse of All Things and hope to have it released in early 2018. I’m working on a novel and have recently rediscovered an old artifact from many years ago that might make for a children’s book. I’m also interested in creating a volume of bird images that may include some brief poetic passages. That project seems to be in the early stages of development. All along, there is the living of this life with all of its lessons, challenges and wonders. And, as always, the work of light-bending goes on.

This article is from The Wayfarer’s 5th Anniversary Collectors’ Edition

Visit our store and purchase the entire issue in print or digital format. It edition features: Wayfarer of the Issue: Krista Tippett, host of On Being. In this extended interview our Editor-in-chief L.M. Browning and Krista, discuss poetry’s role in the current world climate and its place in the husbandry of the soul. Reimagining the Possible: An Interview with Indie Singer-songwriter Melissa Ferrick. The featured photographer of the issue is James Scott Smith. The Mindful Kitchen: Acorn Squash Old Fashioned by Kristen Williams. The Contemplative Column: Contemplating Fatherhood by Theodore Richards. The Environmental Column: Light-Time by Gail Collins-Ranadive. Poetry by: Saizan Owen, Jasmine McBeath, Andrew Jarvis, Ben Colandrea, Elizabeth Bolton, David Amerman, Amy Nawrocki, Jason Kirkey, Ellen Grace O’Brian, J.K. McDowell, David Anthony Sam, Leath Tonino, Dede Cummings, Gunilla Norris, and more!

Do you want more than 1 issue? Subscribe to 1 year of The Wayfarer. Here»

L.M. Browning

Editor-in-Chief, The Wayfarer

L.M. Browning is an award-winning author of twelve books. Balancing her passion for writing with her love of learning, Browning sits on the Board of Directors for the Independent Book Publishers’ Association, she is a graduate of the University of London, and a Fellow with the International League of Conservation Writers. She divides her time between her home along Connecticut’s shore and Boston where she is earning an L.B.A. in Creative Writing and Journalism at Harvard University’s Extension School. Look for Leslie’s next book, To Lose the Madness: Field Notes on Trauma, Loss and Radical Authenticity, Spring 2018. Visit her at www.lmbrowning.com

To bring each issue of The Wayfarer to fruition, it takes hundreds of hours each season to craft, edit, design, and distribute the journal. If you find joy and enrichment within our features, please consider becoming a supporter with a small donation. There is no set amount. Whether it is .99 or a few dollars, we appreciate any gift you care to give. While at this time we are not a non-profit all donations do go towards ensuring the future of the journal.

Help us Empower Change by Giving a Little Change!