The Contemplative Column by Theodore Richards

“Three Girls?!”

I have three daughters. This is generally one of the first things I tell people about myself because it is, I have come to know, the central fact of my life. It is perhaps also true that it is the one thing I can say about myself that will always elicit a positive, or at least sympathetic, response.

But more than a verbal response, I also get a look. I’ve come to know these looks well. They come in two categories.

The first category, admiration, comes when I am out in public with any combination of my three daughters. The bar is low for fathers. As long as I don’t lose one of them and remember all their names, people are pretty much ready to nominate me for the Nobel Peace Prize.

The second category is also gender-related, but it’s more about their gender than mine. This category of response is pity. “You have three girls?” Heads shake. References are made to adolescence, menstrual cycles, and various forms of weaponry I’d be advised to employ when the boys come calling.

These things are always said kindly, and seldom with any awareness of the unspoken assumptions they convey. So I never point out any of the reasons that such statements are problematic. But if I were going to point anything out, I might say the following:

1. Mothers frequently do things like, for example, take their kids to the grocery store, with little praise. I enjoy the accolades, I confess. But sometimes it’s over the top.

2. Adolescence is hard. For girls and boys. It has occurred to me, finally, after years of pondering my discomfort with this, that the real issue here is not that girls are especially difficult—at least relative to boys—but that we fear and despise their bodies., bodies we cannot control in adolescence.

3. They are people, not livestock. Of course we all want our children to be safe, and there are many ways in which girls are targeted and victimized, but it’s important to recognize that sometimes men take on the role of protector as a way of negating the agency of girls. I can’t help but feel that the fixation on whom our girls date or marry devalues them. We just don’t define boys by their partners in the same way. And we don’t think of male sexuality as something to protect, or something to give away. Males are permitted to experience sexuality for their own joy.

What I Teach

I am trying to teach them—and perhaps myself—how to be human. This, of course, is something they are born knowing. But the world then conspires to make them forget.

So we try to do some things that are a little more human than what the rest of the world offers: We break bread together every night and say thank you for what we’ve got. They are seldom on screens. I ask important questions and talk about different perspectives and worldviews. This is their religious instruction—in a post-religious world. I know some people go to church with their kids even though they don’t believe because of all the things one gets out of church. But I just can’t do it. So we practice gratitude together, meditate together, share our feelings, and read about how others have done these things. But above all else, this practice of being human is a practice of listening, noticing, feeling. Of tasting the world. That is a hard thing to teach—impossible, really.

A parent is the child’s first and most important teacher, but this has very little to do with what the parent actually says. What we teach our children is the little world we make for them in our home. We teach with the choices we make about the work we do in the world. We teach through the stories read each night, cuddled together in the bed, a single story—a family—woven together. And each morning, when we are all together in the bed again, a single body.

What I Learn

As is often the case with teachers and students, parents and children, they probably teach me more than I teach them.

My nine-year-old is as capable as most adults in understanding complex ideas. We read old stories together, learn about nature and god, talk about what’s good in a life and what’s wrong with the world. She takes the old stories and tears them apart. She has no patience for patriarchy, for a male god.

They make worlds, all three of them, all-day-every-day. This is a lesson in itself. It teaches me, reminds me, of what I am here to do: To love the world and help create it.

My second child was born three days before my brother died. I learned from her about how death and life, joy and sorrow, come together. This is the central lesson of parenthood, in some ways: that we love our children so much but know that their central task—the thing we are charged to teach them how to do—is to one day leave us. Parenthood is the commingling of paradoxical emotions, and it can be messy.

The messiest day of fatherhood (and this is saying a lot) was the day that my last child was born in my arms in the bathroom. This taught me that we all need to be ready to catch each other when we fall. To care for each other. I won’t forget the blood dripping onto my hands before she emerged, and then how she just slid out so naturally, almost gracefully, into my hands once the head passed through the birth canal.

The head is the hardest part, the biggest part. But my children have taught me that we always get this wrong: we think that what makes us human is the power to think and plan and analyze with our big human brains. This is only part of it. You see, because of this big head the human baby has to come out earlier in the gestation period, when we are still almost embryonic, otherwise we’d never fit. So we are particularly needy. Our minds and hearts and communities are what allow us to survive—we have to care for each other. Without community, without cooperation, we’d never have survived as a species. I might note that this is a process that never ends; we may still prove to be insufficiently compassionate and cooperative to survive. Our big heads can conspire to make nuclear bombs as well symphonies.

The mere fact of their existence is a lesson in the miraculous. Out of nothing—out of us—they are here. One moment quivering and gasping for breath, the next reading novels and building forts, the next writing novels and building bridges. They can see, in their own newness, the freshness and newness of the world. We think, sometimes, that we’ve seen it all. But the world is born new and fresh every day—and this is a bloody and messy process. Through the eyes of a child, we can see this.

This is their gift to me.

I can never repay it.

Fatherhood as Contemplative Practice

The world conspires against listening, and listening is the one thing each parent must do.

So parenting is a practice, primarily, of mindfulness. It asks me, each day, to pay attention. A child—even a single child—demands this of the world: pay attention. This is the thing we seem least able to do in the Modern world.

If we can be mindful, we not only give our child the one gift they really crave, we also can become aware of the miraculousness of existence.

We become aware of the worlds they create each day.

We become aware of the novelty of every moment, perceiving the gift that they bring us: the capacity to find joy and beauty in our world.

Finally, we become aware of the closest thing that I have experienced to what Christians call “grace”: I can make a thousand mistakes—I do make a thousand mistakes, sometimes before breakfast—and still I receive immeasurable, unconstrained love.

Theodore Richards

Editor & Staff Writer

Theodore Richards is the director and founder of The Chicago Wisdom Project, a core faculty member of The Fox Institute, and the author of six books. He is the recipient of numerous literary awards, including two Independent Publisher Awards, The USA Book Award, and the Nautilus Book Award. He lives in Chicago with his wife and daughters. For more information go to his website, www.theodorerichards.com.

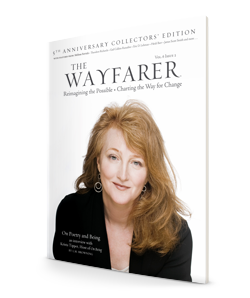

This article is from The Wayfarer’s 5th Anniversary Collectors’ Edition

Visit our store and purchase the entire issue in print or digital format. It edition features: Wayfarer of the Issue: Krista Tippett, host of On Being. In this extended interview our Editor-in-chief L.M. Browning and Krista, discuss poetry’s role in the current world climate and its place in the husbandry of the soul. Reimagining the Possible: An Interview with Indie Singer-songwriter Melissa Ferrick. The featured photographer of the issue is James Scott Smith. The Mindful Kitchen: Acorn Squash Old Fashioned by Kristen Williams. The Contemplative Column: Contemplating Fatherhood by Theodore Richards. The Environmental Column: Light-Time by Gail Collins-Ranadive. Poetry by: Saizan Owen, Jasmine McBeath, Andrew Jarvis, Ben Colandrea, Elizabeth Bolton, David Amerman, Amy Nawrocki, Jason Kirkey, Ellen Grace O’Brian, J.K. McDowell, David Anthony Sam, Leath Tonino, Dede Cummings, Gunilla Norris, and more!

Do you want more than 1 issue? Subscribe to 1 year of The Wayfarer. Here»

To bring each issue of The Wayfarer to fruition, it takes hundreds of hours each season to craft, edit, design, and distribute the journal. If you find joy and enrichment within our features, please consider becoming a supporter with a small donation. There is no set amount. Whether it is .99 or a few dollars, we appreciate any gift you care to give. While at this time we are not a non-profit all donations do go towards ensuring the future of the journal.