From our Spring 2019 Edition | Visit our store to treat yourself to the full issue in either print or digital format. | Browse the Store›

The Wayfarer of our Spring 2019 Issue

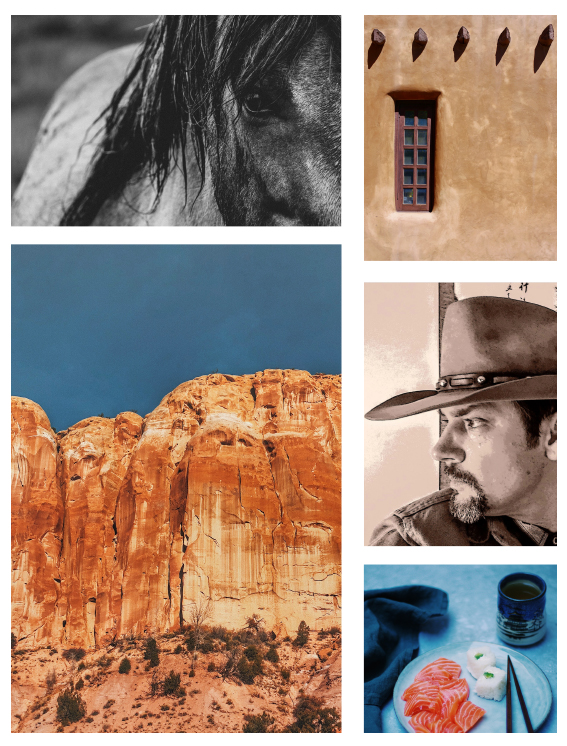

There are certain path crossings that stay with you as fated moments—certain strangers who seem familiar to you–as though while walking through a crowded market, you brush sleeves with someone who knows you but doesn’t know you. This was my experience meeting Frank LaRue Owen Jr. When last we sat together, it was in the dusty high-desert of God’s country. We sipped hot sake and ate sushi made with New Mexico Hatch green chile in a hidden away restaurant at the base of the Sandia Mountains in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and talked of the strange trails we poets find ourselves on in life. Sitting across from him, he is a man removed from the ordinary, insightful yet unpretentious, who is ever-shifting in dimension and depth. He is a poet, descendant of cowboys, and a fellow traveler.

Exploring the origins of his work, Frank LaRue Owen’s poetry is influenced by dreams, the energies of landscape and the seasons, archetypal psychology, the Ch’an/Daoist hermit-poet tradition, and Zen living. He studied for a decade with a Zen woman who—inspired by Ch’an and Daoist tradition—blended silent illumination (meditation), dreamwork, mountain-and-forest spirituality (“landscape practice”), and poetics into a unified path. Owen also studied eco-literature and eco-poetry with the late Jack Collom, a poet and professor in the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado. His first book of poetry, The School of Soft-Attention, was the winner of the 2017 Homebound Publications Poetry Prize. His next offering, Temple of Warm Harmony is forthcoming from Homebound Publications in August 2019.

Leslie: What would you consider your creative origin to be—what confluence of events came about to help you form your poetic voice?

Frank: Some of the very first poetic language I ever encountered was the Tao Te Ching and the I Ching, the latter of which being an oracle from the ancient Chinese tradition. My mother studied the I Ching early in life as part of her Jungian studies and shared it with me in my pre-teen years. In addition to being among some of the oldest expressions of human literature, these works foster a means of thinking symbolically, poetically, oracularly.

On the heels of this, I came across a book in my father’s study entitled Black Elk Speaks, which was already a classic when it fell into my hands. The visionary experiences of this Lakota holy man, and the mystical-poetic language Black Elk used to describe his experiences, were a formative source that shaped me as well. Additionally, Shunryu Suzuki’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind set me on a search early on as a kid.

Putting something to paper myself as a fledgling poet, to translate my own experiences, started in early high school. This was before the internet, of course, so I frequented libraries. Alongside my own poetic experimentation, I studied various sources that supported this endeavor, from the writings of Jung to Joseph Campbell’s The Power of Myth, an extended interview conducted by the journalist Bill Moyers. From that I was led to the poetic language of the Bhagavad Gita and The Upanishads, and this stoked an early interest in world poetry, mystical poetry, and nature poetry, which then led me to the Japanese poet Bashō.

Like so many of our ilk, I’ve also been inspired by the works of Mary Oliver, Gary Snyder, David Whyte, Hafiz, and Rumi. The poems of Joy Harjo, fellow Mississippian Natasha Trethewey, Joseph Stroud, Jim Harrison, and all of the female and male poets of the Chinese and Japanese tradition are never far away.

As for a confluence of events, I would have to say the real crossing of the bridge from being a lover of poetry to a writer of poetry, in earnest, is inseparable from crossing paths with certain teacher figures in my life. They installed a confidence for diving in.

Leslie: Speaking of teachers, you studied eco-literature and eco-poetry with the late Jack Collom, in the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado, which was founded in 1974 by Allen Ginsberg and Anne Waldman. What did you take away from your time at Naropa in a creative sense?

Frank: Mindfulness, and coming into a firm allyship with one’s own heart-mind, undergirds everything at Naropa, from the various psychology programs to the writing program. The main takeaway I received from Jack, in particular, was the practice of deep observation in creative work, on the one hand, and playfulness on the other. Jack was kind of a holy clown in my view, whose creative levity was contagious. He worked with people of all ages around poetry, including little kids in the Poets in Schools movement. Overall, though, what Naropa taught me creatively was permission to create.

Leslie: Beyond traditional learning spaces, we all have mentors who touch us deeply along our journey. You speak of a “Zen woman” your path converged with out in the mountains of New Mexico—a landscape of deep magic in and of itself. Would you mind telling us a little about this meeting and the impact this relationship had on your creative work?

Frank: Known as doña Río to some of us, Darion was a truly remarkable person who touched many lives in different ways. She was chameleon-like in her interests and in the methods she used in her guidance work with individuals and groups, which she loosely called “life path exploration”. She would take on different qualities and emphasize different approaches depending upon who she was working with, and this included various methods from Asian spiritual traditions, Mesoamerican sources, wilderness rites of passage work, and Jungian psychological models.

Reflective of this, for example, in my first phase of knowing her (the early and mid-90s in Colorado), we worked almost exclusively with Zen practice; namely silent illumination meditation, meditation on phrases (known as huatou/wato in China and Japan), and frequent knee-to-knee interviews that Japanese tradition calls dokusan. When I look back on that time, I think she was just setting the stage for things to come, along with trying to help me become more of an ally to my own heart-mind.

Later on in the late 90s and 2000s, after a life detour on my part to D.C., and a move to New Mexico by her, at which time she became more hermetical, her work with me shifted. With a firm foundation of meditation having become second nature, the work became more focused on landscape and dreamscape, and poetics was a means of processing experiences with both. I made frequent cross-country trips each year to New Mexico to study this Southwestern “green chile Cowboy Zen” with her, including whole months at a time, and “the classroom”, the “zendo”, so to speak, was a mix of time in an adobe house in Santa Fe, time in the forests of the Pecos Wilderness, and time out in the desert.

Despite knowing her as well as I did, she remains a mysterious figure to me. She was very much a horse person, was constantly doing dreamwork throughout the day (because, in her own words, “We’re never not dreaming”), but I only know small fragments about her life, which included her own experiences studying with Ch’an and Taoist teachers, and trips into southern Mexico to study with a curandera and a seer.

Leslie: You follow in her footsteps as a “mysterious figure.” You seem a modern-day, reclusive, Zen hermit-poet more suited to the age of Ryōkan than that of this era. How do you see yourself within the current poetic landscape?

Frank: I definitely have a need and a leaning for solitude. It is how I refuel and solitary time is when I am afforded the potential to delve into the creative process. In general, I find many aspects of modernity overwhelming, if not downright insane, so there is a lot about the world I don’t engage with. But, that said, I wouldn’t call myself a recluse because I still enjoy being around people and have a commitment (at least for now) to stay engaged in the world and remain connected to community, such as it is.

I’m also not a true hermit by most people’s idea of the term, but I do live a pretty solitary existence, and, at times, have emulated the lifestyle of certain early Ch’an poets who lived in urban settings, held day jobs, but stayed to themselves at night and went on mountain retreats as often as they could to focus on their poetry and Zen practice.

A lot of this may be a natural leaning for me, since even in my senior year of high school I avoided typical high school activities. I would come in from the day, drop my books, and head straight out into the forests behind my mother’s house in North Carolina.

Being a solitary in recent years is also due to circumstance. From 1995 to 2005, I was very active out in the world. In fact, I was facilitating retreats along the themes of dreams, consciousness, contemplative practice, nature, and ecopsychology. However, in 2005, and especially in 2007 when doña Río died, I intentionally turned inward. Initially, grief was the motivator. But, then I began exploring the biographies of certain hermit-poets and felt an immediate affinity with how they had arranged their lives.

Some years I would put this exploration on the back burner and, for example, focus on relationship. Other years, my creative process has been the only thing for which I have held space. Both types of cycles have taught me a great deal.

This year, I’m crossing into my 50s, and also clocking my fourteenth year of wandering down the same path I began walking with doña Río, spiritually and creatively. I have no idea where it is all going. As I age, living a slower pace becomes even more important to me; to connect with the land, to practice Zen, to explore ancestral energies, cultural streams, and heritage, and to write. But, yes, most days I feel like you could probably drop me in a Japanese forest or back behind a mesa in New Mexico, and I’d be okay.

Where this places me in the poetic landscape I’m not entirely certain. Perhaps one way of putting it is this. All poets are oriented to paying attention. They are attuned to the life around them. I am as well, but I’m also oriented to the life of nature, the inner life, and other non-obvious realities.

Leslie: Delving into your practice of holding space, tell us about your creative process.

Frank: My creative process is definitely a lived and living experience. Various natural images come to mind that express this. Climbing a mountain. Disappearing into a forest enveloped in clouds. A river that has its own particular flow but which also reflects, in some sense, what it encounters as it flows along.

At times, my creative process has felt like attending to a rather cosmic relationship; to what East Asian cultures call the Dao (Tao, The Way). As I say in the Preface of The Temple of Warm Harmony, “…’round and ‘round the sun-like Dao.” Sometimes that is what my creative process has felt like.

Lately, the working metaphor for my creative process has been riding a horse. Writing has begun to feel akin to saddling-up, heading out on a trail, and journeying beyond known trails into uncharted territories. In some cases, the “horse” is the horse of memory, taking me back into childhood, or into the multidimensional muscle memory and memory of the senses that gets registered when visiting a place.

I’m currently working on my third book, Stirrup of the Sun & Moon, which is tethered to experiences of memory of mind, dream, and place. My heart-mindstream is awash in a cascade of images, insights, and impressions, so my creative process has become one of registering these impressions, sifting through them as if panning for gold. A few of these kinds of poems have made prior appearances, such as “Quantum Travel” in The School of Soft-Attention (2018), but now I’m following the thread more closely where mindscape, dreamscape, and landscape touch.

Practically speaking, I wake up with my creative process every day because the moment I awake I am processing impressions from the dreamtime. So, notetaking, journaling, and trying to pull dream vignettes and fragments through the permeable membrane of consciousness that separates the dreaming and waking worlds is part of my daily course. That, and talking out loud to myself. [Laughs]

I live alone so I may even talk out loud to myself as a means of conjuring flashes of the dreaming mind so as to bring through the images that were experienced in a dream, or that are still fluttering about at the periphery of awareness in the dreaming body (which, of course, extends beyond the physical body). This activity is really rooted in the technique of active imagination from the Jungian tradition. It works well with dreams, it works well with poetry, and some day I hope to apply it to the realm of fiction.

Leslie: What do you think the role of the poet is in the current world climate?

Frank: We are living in a truly disturbing time. Not to oversimplify current conditions, or add unnecessary layers of lathered-up fear, but the energetic reality we are in strikes me as a battle of wills, conscience, and consciousness.

There are some whose consciousness is on a destructive footing. Destructive of earth. Destructive of societal, economic, and governmental norms. Others of us reject this on civic, environmental, and humanitarian grounds.

The poet in such times is what the role of the poet has always been: serving as a collective conscience (not holding our tongue about injustice, for example), but also reminding us all that, despite the presence of despots of delusion and dysfunction, that the numinous level of reality—of beauty, of grace, of healing, of sacred mystery—still exists, and will endure.

In this way, the poet can be a healer, a transmitter of perennial wisdom, and a culture of harmony rather than degradation and divisiveness. Indeed, as both conscience and purveyor of elevated consciousness, the poet can remind us all who we really are, individually and collectively. It seems to me we need both of these functions now more than ever.

Leslie. What words of hard-earned wisdom would you impart to those creative minds still seeking out their voice and getting ready to “saddle up” and head out onto the trail?

Frank: Become an apprentice to your deeper self. This includes one’s dreams and the wise characters found therein. It also includes checking in with yourself multiple times during the day. Surface world technological distractions can be a real obstacle to such deeper attunement. There is a natural human wisdom inherent in the person that practices mindful attentiveness. Make it a practice.

Trust that one’s own voice is linked to one’s creative process, which has a life of its own. It has its own flow; you’re just along for the ride. You can paddle and steer, but you can’t push the river.

Trust that one’s voice and creativity has a purpose that has its own seasons and rhythms. Live closely according to those rhythms. Live in attunement with the seasons of your creative life. Honor the fallow times just as much as the inspired and abundant times of creative harvest.

When it comes to creative writing, eject modernity’s cold, lifeless notions of writing being mechanical and product focused. If you want to do writing like that, get a job in advertising.

I would also add, try holding the notion that writing (or any creative endeavor) is not an exclusively intellectual exercise. Try on the experience of writing as a full-bodied somatic experience including giving voice to hunches, impressions, 24/7 lucid dreaming, like picking up flavours and aromas from the ethers. Creativity can be a multidimensional experience involving senses beyond just the five we usually rely upon.

Held in this way, there is no such thing as writer’s block. Even when you aren’t actively writing, you realize you’re working, or are ‘being worked,’ by the larger process; what I call “the poet’s dreaming body” is actively working, observing, recording, seeing. Learning to trust in that feels related to trusting one’s creative voice. Don’t dismiss anything in your experience.

L.M. Browning

Editor-in-chief, The Wayfarer

L.M. Browning is the Founder of The Wayfarer Magazine, TEDx Talker, award-winning author of twelve books. Balancing her passion for writing with her love of learning, Browning sits on the Board of Directors for the Independent Book Publishers’ Association, she is a graduate of the University of London, and a Fellow with the International League of Conservation Writers. She is currently earning a degree in Creative Writing at Harvard University’s Extension School. Look for Leslie’s next book, To Lose the Madness: Field Notes on Trauma, Loss and Radical Authenticity. Visit her at www.lmbrowning.com

Related Articles

12 Tiny Things, Two Open Hearts

Meet 12 Tiny Things authors Heidi Barr & Ellie Roscher, interviewed by Wayfarer Editor Leslie M. Browning | From the Spring 2021 Issue

Our Angel of the Get Through | An Interview with Andrea Gibson

From our Autumn 2019 Edition | Visit our store to treat yourself to the full issue in either print or digital format. | Browse the Store› The Wayfarer of our Autumn 2019 Issue | Shop Now All Rights Reserved. Our Angel of the Get Through A Conversation...

Belonging to the Land: A Conversation with Stephen Trimble by L.M. Browning

From our Spring 2019 Edition | Visit our store to treat yourself to the full issue in either print or digital format. | Browse the Store› The Wayfarer of our Spring 2019 Issue - All Photos courtesy of Stephen Trimble. All Rights Reserved. Stephen Trimble tells...

Stay Up to Date With The Latest News & Updates

Subscribe

We offer our biannual issues in both print and digital editions.

Explore. Replenish. Inspire.

Join Our Newsletter

The Wayfarer posts new content weekly and releases two print issues a year on the first of Autumn and Spring, respectively. Sign up for our free monthly digest of the month’s most inspiring articles across nature, poetry, personal essay, and more as we continue on our mission to foster a community of contemplative voices and provide readers with resources and perspectives that support them in their own journey. Sign Up Below:

Follow Us

Join us in our digital communities.

learn more

Write Us

Get IN touch

(860).574.5847

The Wayfarer Magazine

PO Box 1442, Pawcatuck CT 06379-1442

With Basecamps in:

- Mystic, Connecticut

- Las Vegas, Nevada

- Cambridge, Massachusetts