A New Column by Eric D. Lehman

Recently, I was wandering through a vaulted museum hall, steel and concrete and glass packed with abstract sculptures that look vaguely like intestines, paintings resembling organized vomit, and lines of bored schoolchildren, and I realized this is what people think of when they think of “the arts.” That misconception makes it so much easier to attack them as dangerous, as garbage, or as an indulgence for the idle habits of a spoiled bourgeois. When art programs are cut from schools, administrators and parents shrug, imagining the uselessness of training children to make collages or play the oboe. No one thinks we are engaging in “the arts” when we binge-watch Game of Thrones or fill our ears with a selection of favorite hip-hop tunes. But we are.

When we talk of benefits as somehow being monetary or not, survival or not, we miss the point entirely. Without the arts, we are doomed to live on the surface only, at the most basic level of existing. From the blown paint on the cave walls of southern France to the stained glass of Chartres, from the shepherd’s flutes of ancient Egypt to the electric guitar of Jimi Hendrix, the arts have always been the truest, most human pursuits. They raise us above the political dialectic of the moment, above the mundane, repetitive labor of life, above our own weaknesses.

The art we create and encounter also has the most to teach us, the most to give to future ages. When speaking just before World War II, an amateur watercolorist named Winston Churchill told the Royal Academy, “Here you have a man with a brush and palette. With a dozen blobs of pigment he makes a certain pattern on one or two square yards of canvas, and something is created which carries its shining message of inspiration not only to all who are living with him on the world, but across hundreds of years to generations unborn. It lights the path and links the thought of one generation with another, and in the realm of price holds its own in intrinsic value with an ingot of gold. Evidently we are in the presence of a mystery which strikes down to the deepest foundations of human genius and of human glory.” Few have said it better.

All this may be true, yet often fails to convinces anyone that “the arts” are important to our own lives. Why should we care? Let us instead speak on a more fundamental level. Our interaction with “the arts” begins as soon as we are born, with the whispered metaphorical words of a mother to a daughter. “You are my angel.” The picture of a dragon a child draws for his father, who displays it proudly on the refrigerator. The song sung by two lovers in the night. The television show shared by a family who disagrees on everything else. The film that makes you cry every time you see it. These things are not extraneous, not escape, not a distraction from some cause. They are the ultimate goal of the cause—a life worth living.

Every human animal is an artist in his or her perceptions. Whenever we appreciate the story or characters of a television show, we engage with the artistic process, despite lumping it into “entertainment” with other barely related activities. My brother Andy plays his favorite songs while he performs complicated orthopedic surgeries for many reasons—nostalgia for the past, camaraderie with the nurses, relief from stress, and aid to concentration, among others. He loves to talk about why a certain song or another is great. In doing so he is engaging both emotionally and intellectually with the art form that moves him most. Whether you are trying to understand Picasso’s Guernica or figuring out which photograph of your dog to post on the internet, you are engaged in an act of art appreciation.

This can be rewarding on its own, and in my brother’s case we can see how creative analysis and ability to multitask makes him both a better surgeon and a better person. It could also inspire further production of art—he may not be a musician, but his children certainly are. To be writers we need to first be readers, that is clear. And though experiencing art is one of the great joys in life, creating it can be even more satisfying. Before the agricultural and industrial revolutions, almost everyone engaged in some kind of creative work. Our increased specialization means that fewer and fewer people engage in the arts as their primary or secondary job. Instead, for most people they have become “hobbies.” In addition to the creativity necessary for cooking, bringing up children, and making a home, my mother-in-law Ferne quilted, stenciled, and made clothes from scratch. She considered them “hobbies,” though that slightly foolish Middle English word does not do justice to these activities.

You don’t have creative hobbies? You don’t take photographs? You don’t dance when music comes on? You don’t tell funny stories to your friends? Of course you do. The arts are deep within each one of us, and whether we realize it or not, we engage in creative acts every day, whether mixing a drink or tending a garden. We begin as children, using our imagination, making up stories, play acting, singing out loud. Most of my early childhood was spent creating fantasy worlds in the basement with my brother or with my friends in the cornfields behind our house. And in my “hobby” as a writer, I attempt to continue that process, not to get back to my childhood but to remain fully human.

There are a handful of activities that really distinguish us as human and nearly all of them involve creation or discovery. It doesn’t matter if you’re performing Mozart’s symphonies or turning wood in your garage, anything creative makes life more than just survival. The arts give each person a sense of individuality and uniqueness, and at the same time give us the sense that we are contributing to humanity, even if our only “audience” is our family. My brother-in-law Michael is a detective, and like most jobs, his requires creativity. But his artistic pursuit is cooking. Whenever he gets a chance, he focuses his energies on smoking ribs and chicken, crafting amazing meals from myriad elements. He has inspired his daughter’s love of baking, and provided innumerable delicious creations for his lucky family and friends like me. His life is invaluably enriched by the imaginative culinary art he practices, and also by the steady improvement of his skills as a chef. The more you focus on improving skills the more they help your mind and spirit. However, while quality is an objective, the arts are not a game—there is no winning or losing—and you don’t have to be an expert to be creative, or to experience its benefits.

The act of making something that was not there before is satisfying on its own. But the arts do even more for us—they craft a sense of self. A friend and chemist named Amanda talks of the act of painting as her energy becoming physical, while rooting her in the moment. In this way art also forces us to pay attention to things, to be more aware, in the same way that mindfulness meditation might. Another friend Kristen, biologist by day, builds furniture out of old wood pallets, finding working with her hands peaceful and relaxing, a moving contemplation. The process prepares our spirits for the big tasks of life, for the moments when the world tests our courage, our wisdom, our strength. Synthesizing experience and information and building new things from it also enlarges our brains, a long-held truism that neuroscientists can now call fact. And the process builds—the greater our sense of self, the more we create, and thus the greater our sense of self.

None of these people—Andy, Ferne, Michael, Amanda, Kristen, or Winston Churchill—are considered artists by society. And that is the point. We all use our imaginations to live, and live to use our imaginations. The arts are simply the volcanic eruptions from that deepest part of life, the fiery core of our own earths. Creativity flows like magma, changing our surfaces, burning away our lies, our failures, our hates. Sometimes we can get there by reading, or listening to music, or binge-watching a show. But we certainly can get there by drawing, by dancing, by acting. By bringing as yet unknown beauty into the world.

So, use that internal lava and build islands in the Pacific. Put a pen to paper or a hammer to iron. Scoop out your marrow and spread it on the canvas. Focus your eyes, your hands, your mind. Take a hundred styles and stir-fry a new form into being. Communicate, connect, synthesize. Grow a new limb or two while you’re at it. After all, that’s what your very cells are urging you to do. Engage in the arts. Begin to be. Become.

Eric D. Lehman

Associate Editor & Staff Writer

Eric D. Lehman teaches creative writing and literature at the University of Bridgeport and his work has been published in dozens of journals and magazines, from Berfrois to Gastronomica. He is the author of twelve books of fiction, history, and travel, including Shadows of Paris, Homegrown Terror, Afoot in Connecticut, The Foundation of Summer, and Becoming Tom Thumb. Eric D. Lehman teaches creative writing and literature at the University of Bridgeport and his work has been published in dozens of journals and magazines, from Berfrois to Gastronomica. He is the author of twelve books of fiction, history, and travel, including Shadows of Paris, Homegrown Terror, Afoot in Connecticut, The Foundation of Summer, and Becoming Tom Thumb. Visit his website at www.ericdlehman.org.

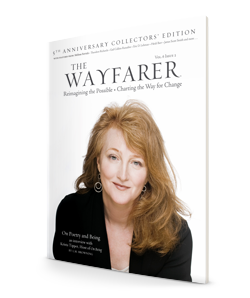

This article is from The Wayfarer’s 5th Anniversary Collectors’ Edition

Visit our store and purchase the entire issue in print or digital format. It edition features: Wayfarer of the Issue: Krista Tippett, host of On Being. In this extended interview our Editor-in-chief L.M. Browning and Krista, discuss poetry’s role in the current world climate and its place in the husbandry of the soul. Reimagining the Possible: An Interview with Indie Singer-songwriter Melissa Ferrick. The featured photographer of the issue is James Scott Smith. The Mindful Kitchen: Acorn Squash Old Fashioned by Kristen Williams. The Contemplative Column: Contemplating Fatherhood by Theodore Richards. The Environmental Column: Light-Time by Gail Collins-Ranadive. Poetry by: Saizan Owen, Jasmine McBeath, Andrew Jarvis, Ben Colandrea, Elizabeth Bolton, David Amerman, Amy Nawrocki, Jason Kirkey, Ellen Grace O’Brian, J.K. McDowell, David Anthony Sam, Leath Tonino, Dede Cummings, Gunilla Norris, and more!

Do you want more than 1 issue? Subscribe to 1 year of The Wayfarer. Here»

To bring each issue of The Wayfarer to fruition, it takes hundreds of hours each season to craft, edit, design, and distribute the journal. If you find joy and enrichment within our features, please consider becoming a supporter with a small donation. There is no set amount. Whether it is .99 or a few dollars, we appreciate any gift you care to give. While at this time we are not a non-profit all donations do go towards ensuring the future of the journal.