The Enviromental Column

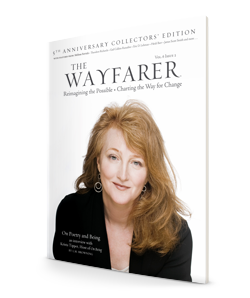

(Photo Above my Issue Feature Photographer, James Scott Smith)

Binge reading back issues of The Wayfarer for this essay, I sit out on my Southern Nevada patio in light that is so vivid I can almost believe that it is just now reaching the earth from the very beginning of time.

Unobstructed and unfiltered by trees, the clarity of light in the arid west sparks my imagination: what if the quantum physicists are right?

If we could ride a beam of light as an observer, would all space shrink to a point, all of time collapse into an instant?

Would I be able to perceive the past, present, and future as through a singular lens?

All at once my Wayfarers morph into The Dial, the contemplative journal edited by Margaret Fuller and Emerson.

Fuller, a proto-feminist far ahead of her own time, is gently rejecting an early poem from Thoreau in hopes that:

He will seek thought less and find knowledge the more. I can have no advice or criticism for a person so sincere; but, if I give my impression of him, I will say, “He says too constantly of Nature, she is mine.” She is not yours till you have been more hers.

Like The Dial, The Wayfarer publishes authors who ‘belong’ to Nature. Reading their offerings as deliberately as they were written, exactly as Thoreau advises, I too can contemplate the mystery of an ancient yew in Scotland, marvel at the light in a mountain in Ireland, imagine my feet in the salty sea of coastal Connecticut and the surf off Cape Cod, enter into the silence of the winter solstice retreat in Michigan, peep at autumn leaves, and listen to the ‘throaty’ sound of wooden pencils celebrating Thoreau’s birthday. Open any issue of The Wayfarer and out will spill herbs or weeds, humming birds or lambs, bears or rattlesnakes, horseshoe crabs or seals, lots and lots of coyotes.

Then as now and now as then, contemplation of nature can create an ‘enlightened’ human, one in-tune-with the Earth’s dynamics through intuition, insight, and ideas as Time’s Light shines through the prism of the human mind, heart, and spirit.

Outer senses reacting to the natural world can activate inner senses that lead to self-reflection, that uniquely human attribute that appeared sometime in the Pleistocene Age, when something within us turned back on itself and so to speak took a giant leap forward, as Teilhard de Chardin once put it.

For Emerson, nature was the vehicle for the process of self-reflected awareness, convinced as he was that what is beyond nature is revealed to us by nature itself.

Yet when his infamous essay Nature was published in 1836, Andrew Jackson was in his final year of a presidency that championed the ‘common man’ over the intellectual elite, and states rights as an antidote to federal corruption.

Defying the Supreme Court, Jackson set in motion the Indian Removal policy that would result in the Trail of Tears: gold had been discovered on Cherokee land.

Nature’s blessing had become its own curse.

When Emerson’s Self Reliance was published in 1841, it could be read as a pep talk that Emerson gave himself because he was suddenly ‘out of sync’ with the emerging mindset of the macho frontiersman. After all, he had been trained for the ministry, by then considered an ‘effeminate’ profession.

In another five years the United States would provoke a war with Mexico, and Manifest Destiny become our national mission. And that fool Thoreau would refuse to pay his taxes because he won’t support that war, even if it meant spending a night in the Concord jail.

While the existing United States really only wanted easier access to California’s gold, we also acquired Arizona, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Colorado in the bargain.

We who live in the American West pick up where Thoreau left off and give ourselves Emerson’s Self Reliance pep talk as we try to preserve and protect the last of our public lands from gold and uranium mining, cattle grazing, and the coal, oil, natural gas exploitation that’s changing the global climate.

Trusting ones inner vision takes clarity; translating it into outer action takes courage, and the Transcendentalists provide role models. For them, sacred awareness became social activism. We can follow the same trajectory in articles found in The Wayfarer, from Sandy Hook to Standing Rock, with reimagining the possible as the vision and where rewilding is a way into a sustainable future. For as Thoreau put it: in wilderness is the preservation of the world.

These are not identical, of course: one is a place; the other is a way of being. Set-aside wild places provide space for the growing edge of human imagination to come to fruition. And as Brian Swimme tells us, the human imagination is how the future reaches into the present and shapes itself.

Holding this thought ‘in the light,’ I can reimagine this: Emerson is visiting John Muir in California. It is 1884. Muir is half Emerson’s age; in fact, he’d read Nature while in college. Now he gets to show his hero the great trees and share his own reverence of the giant redwoods. Riding horseback into the wild, Muir finds himself doing what many of us might do as well: quoting Emerson to Emerson, in excerpts from Nature.

Then he adds: “You yourself are a sequoia. Step up and get acquainted with your big brother.” Muir dearly wants Emerson to spend the night camping in this wilderness that’s already been protected by Lincoln, as a land grant for public use and recreation. But Emerson’s entourage wouldn’t hear of letting the 68-year-old sage sleep out in the cold on the cold hard ground. Wistfully, Emerson acquiesces, and responds with, “The wonder is that we can see these trees and not wonder more.” That wondering bares fruit some eighty-eight years later, when Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas gives the dissenting opinion in the legal struggle against destroying acres of protected sequoias in order to construct a ski resort.

In Sierra Club v. Morton, the case in which the constitutional right of concerned citizens to sue on behalf of the great trees was questioned, Douglass declares that:

“Contemporary public concern for protecting nature’s ecological equilibrium should lead to the conferral of standing upon environmental objects to sue for their own preservation. The voice of the inanimate object, therefore, should not be stilled, that before these priceless bits of Americana (such as a valley, an alpine meadow, a river, or a lake) are forever lost or are so transformed as to be reduced to the eventual rubble of our urban environment, the voice of the existing beneficiaries of these environmental wonders should be heard.

Those who hike the Appalachian Trail. or run the Allagash in Maine, or climb the Guadalupes in West Texas, or who canoe the Quetico Superior in Minnesota, certainly should have standing to defend those natural wonders before courts or agencies, though they live 3,000 miles away. Then there will be assurances that all of the forms of life which it represents will stand before the court—the pileated woodpecker as well as the coyote and bear, the lemmings as well as the trout in the streams.

Those inarticulate members of the ecological group cannot speak. But those people who have so frequented the place as to know its values and wonders will be able to speak for the entire ecological community.”

Today, with our public lands under assault by the very government responsible for protecting them, we the people are fighting for them harder than ever. Without wild places, the biodiversity of our planet is diminished, as is our humanity itself. Biologist E.O. Wilson claims that we must set aside not just disconnected parcels of land but half the earth for other than human species. Is this an impossible dream in a world where the dominant religion is consumerism and we’ll need more than one planet to maintain our current affluent lifestyle?

I squint into the light, trying to see into the future. But it is a blinding white…a blank page that’s yet to be written upon? My armful of issues of The Wayfarer reminds me that its writers and readers are a community of wanderers charting the way for change. Within the pages of this publication, where the light from the beginning of Time that became all Life on planet earth continues to spark enlightenment, the future well may unfold in upcoming issues. Stay tuned.

Gail Collins-Ranadive

Columnist

Gail Collins-Ranadive, MA, MFA, MDiv, is a retired Unitarian Universalist minister, a former nurse, a licensed private pilot, and a workshop facilitator. Author of seven non-fiction books, including Chewing Sand and Nature’s Calling, she writes the environmental column for The Wayfarer. An Easterner by birth and a Westerner in spirit, she and her partner winter at her home in Las Vegas and summer at his in Denver. Gail is the mother of two and the grandmother of five. Visit her at www.gailcollinsranadive.com

This article is from The Wayfarer’s 5th Anniversary Collectors’ Edition

Visit our store and purchase the entire issue in print or digital format. It edition features: Wayfarer of the Issue: Krista Tippett, host of On Being. In this extended interview our Editor-in-chief L.M. Browning and Krista, discuss poetry’s role in the current world climate and its place in the husbandry of the soul. Reimagining the Possible: An Interview with Indie Singer-songwriter Melissa Ferrick. The featured photographer of the issue is James Scott Smith. The Mindful Kitchen: Acorn Squash Old Fashioned by Kristen Williams. The Contemplative Column: Contemplating Fatherhood by Theodore Richards. The Environmental Column: Light-Time by Gail Collins-Ranadive. Poetry by: Saizan Owen, Jasmine McBeath, Andrew Jarvis, Ben Colandrea, Elizabeth Bolton, David Amerman, Amy Nawrocki, Jason Kirkey, Ellen Grace O’Brian, J.K. McDowell, David Anthony Sam, Leath Tonino, Dede Cummings, Gunilla Norris, and more!

Do you want more than 1 issue? Subscribe to 1 year of The Wayfarer. Here»

To bring each issue of The Wayfarer to fruition, it takes hundreds of hours each season to craft, edit, design, and distribute the journal. If you find joy and enrichment within our features, please consider becoming a supporter with a small donation. There is no set amount. Whether it is .99 or a few dollars, we appreciate any gift you care to give. While at this time we are not a non-profit all donations do go towards ensuring the future of the journal.