The Kennedy Center

A Legacy of Grassroots Compassion

by L.M. Browning with Kelly Kancyr

The Kennedy Center was founded in 1951. It stands as a testament to the force of a small group of dedicated citizens to impact change in our communities. The organization was established by Evelyn Kennedy and twelve parents who decided to take matters into their own hands and ensure an educational and support system for their children with disabilities. At the time, in 1950s America there were no such supports in place. The convention of the time, held by medical experts and society as a whole, was to simply institutionalize children with developmental disabilities. Undeterred by such common practices, Kennedy envisioned a better world, where children suffering a disability would have the same opportunities in life as every other child. Together, Evelyn Kennedy and this core of visionary parents created an organization with a rich tradition of grassroots innovation, staunch advocacy and expansive volunteerism.

Spearheading a new approach Kennedy and the co-Founders filed for incorporation. Bound and determined to provide educational classes for their children, this courageous group of parents remained united in their effort to help their children. Before 1951 ended, they would be responsible for the first classes for children with developmental disabilities in public schools in New England. Soon after, their ground-breaking accomplishments resulted in the creation of New England’s first parent-sponsored, public school facility for children with developmental disabilities. The school opened its doors in 1956, in a small house on Williams Street in Bridgeport, Connecticut. The first building took 18 months to complete with 80% of the construction being accomplished by the organization’s parents and friends.

In the short time from the organization’s humble beginnings, the founders became responsible for writing Connecticut legislation that made it mandatory for school systems to provide educational services for children with developmental disabilities. Throughout the 1970s, with the ever-increasing numbers of individuals coming into the organization, the center moved to a larger building, academic programming was established, speech therapy classes commenced, and vocational rehabilitation programs were initiated. Still, the founders and their network of community volunteers continued to provide the momentum for the future of the organization. Two of the most important occurrences of the decade include when Frank and Fred Ahlbin donated their Garden Street factory building in Bridgeport to become the new headquarters of the organization in 1976. Then in 1978, the Board of Directors decided to hire a new President and CEO to enlarge the regional services and to expand the age group of consumers. Martin D. Schwartz was hired as the new CEO and President, which proved vital to moving the organization forward to a higher level of productivity and expansion. As stated by Evelyn Kennedy “ Marty Schwartz moved the organization to the level of expertise, competency, and recognition that made The Kennedy Center name synonymous with excellence.”

The organization’s program services expanded well beyond developmental disabilities in the 1980s. Societal perception of individuals with disabilities was also changing. Over the years, the organization developed strong relationships with the Connecticut Department of Mental Health, the Department of Children and Families, the Department of Social Services, and the Bureau of Rehabilitation Services. The age range of the individuals being served was extended from birth through senior years, and Community Experience programs were created for individuals with multiple and severe disabilities.

By the early 90’s, The Kennedy Center had added a Cooperative Living Arrangement, a Supported Living Option, and a private rehabilitation program for workers that were injured on the job to its list of achievements. Meanwhile, Children’s Services were expanded while travel training and transportation services were being launched. Once again the organization would have to move to a larger facility to accommodate its expansion. On the December 31st, 1992, The Kennedy Center acquired a new corporate office on Reservoir Avenue in the town of Trumbull, where it remains today. In every case, the established Kennedy Center tradition of practical improvements, based on everyday experiences, led to innovation and excellence.

In 1990 the organization received an Exemplary Program Award from Rehabilitation Services Administration of the U.S. Department of Education. By 1999, Evelyn Kennedy and The Kennedy Center had received one of six nationwide Special Achievement Awards from the National Rehabilitation Awareness Foundation, Evelyn Kennedy received the first Connecticut Treasure Award from Lt. Governor Jodi Rell, and it was the only agency in Connecticut to ever receive a perfect accreditation rating from Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities. The Kennedy Center would achieve this rating again in 2002, which placed it in the top 1% of rehabilitation facilities in the United States.

While The Kennedy Center has received a host of awards for its exemplary model of excellence over the past six decades, in the past seven years The Kennedy Center received the Connecticut Martin Luther King Humanities Award for Travel Training Program in 2004; the Christina Lewis Award from the Department of Social Services in 2005.

In 2011, The Kennedy Center celebrated its 60th Anniversary and continues the legacy established by its founders.

***

As I arrived at the headquarters in Trumbull, Connecticut, my liaison for the day is Counseling Services and Career Development Manager, Kelly Kancyr. Kelly has been working with the Kennedy Center for almost 3 years. She is the Supervisor of the Vocational Case Managers, that work with individuals who are employed. It is my intention to learn more about organizations such as Kennedy Center, the passion at the heart of their workers, the needs of the community they serve, and the impact of ever-shrinking budgets on their ability to provide services. Over the course of my day, I will speak with Kennedy Center President Martin D. Schwartz, Vice President of Rehabilitation Services, Valarie Reyher, and Vice President of Kennedy Industries Lynn McCrystal but first, I asked Kelly to help me meet the heart of the Kennedy Center: the individuals within this vibrant community who attend these diverse programs.

It’s early in the morning, the staff is just arriving, and the cafeteria is full of people awaiting the start of their day. The mood of the room is one of worry. At present, the state of Connecticut is in a budget crisis and The Kennedy Center has been forced to give their staff a furlough day once every few weeks. During these furlough days, the individuals who depend on Kennedy Center for both job placement and day programs stay home.

“I just want to be able to work,” Amanda Soleck tell me. She is in her 30s and a member of Kennedy Center. “I want to come in each day and know that I will have a job. I like working.”

This sentiment is understandable to us all. Some days, individuals who attend Kennedy Center will work, others they will be asked to volunteer their time unpaid. Consistency is a huge issue. Imagine waking each day and not knowing if you were going to work; if so, where you would work; who you would be working with; and if you would be paid.

Pay and social security is balanced to ensure that each individual has the money they need to survive; however, the individuals I spoke with are eager to work and grateful for a permanent position. The problem: jobs simply cannot be found. Kennedy Employment Services works tirelessly to find placement for the individuals who attend Kennedy Center. It is just hard to find employers willing to diversify their workforce and hire a person with an intellectual disability.

Speaking with Valerie Reyher, I get an idea of the dedication it takes to do such an emotionally taxing job day after day and the ingenuity required to work in the face of small budgets and ever-widening need. Reyher confirms what I suspected, it all begins with passion:

“I always enjoyed interacting with people, talking to people. It started out as somewhat as that venture, thinking like, ‘Oh, I could help someone.’ My parents were divorced and it was nice to find commonalities with people and potentially help them through that process. In my senior year of high school, one of my very close friends had an aneurysm. And I started to learn about her rehabilitation and then I had the opportunity to take some psychology courses at Colgate University and just kind of fell in love with it.

And from there I went on to Marist College and my true passion definitely came in with brain injury and neuropsychology. In my college years I had the opportunity to work with some career counselors, and that really moved me more into vocational rehabilitation that I’m not just in that mode of a caretaker, but I’m helping people achieve goals. I’m helping people advance to the next level of their lives. And it just became a passion for me. I just really enjoy it, and the opportunity to work with all disability populations has just really been extremely rewarding for me.”

Reyher is Vice President of the Rehabilitative Services. The mission of the rehabilitation division is to assist individuals with obtaining employment and to increase one’s independence in the home and community. Speaking to the difficulties inherent in this mission, Reyher says plainly, “Funding restrictions . . . all the time. I think that’s the hardest piece. At Kennedy Center, we have great staff—we have people who want to do this job—but they can’t afford to live on these salaries, so keeping them motivated is a day to day challenge.”

One of the aspects of Reyher’s division is KES “Kennedy Employment Services” the purpose of which is to assist members of the Kennedy Center community with job placement. A new initiative is to have recent graduates enter a transition program wherein they obtain the skills to acquire a competitive wage job.

After speaking with members of the community myself, I can tell they take pride in their work and are eager for the consistency of permanent job placement that allows them to contribute towards their own cost of living. When asked what she would like potential employers to know about the individuals Kennedy Center serves, she ardently replies, “We have capable, competent individuals that aren’t necessarily looking to jump and advance as quickly as the ‘average person.’ They are loyal to their employers. They are grateful for having a job.

Most people . . . when you talk about a job, it’s a job. It’s great. I can always get another one. The folks that we serve appreciate that this is work. I have it. I’m lucky to have it. And they like the work that they do. And when people like the work that they do, they’re going to continue to do it.

I also want employers to know that a disability can happen to anyone. And if they can put themselves in those shoes of what opportunities would they want if they were in that situation, would they want somebody else to limit them? Would they want somebody to say no, because you have a label of a diagnosis? Would they want somebody to seek pity on them? Nobody wants that. People want to return to work or obtain work or sustain work as much as possible. And I think it’s something that we take for granted. Until you don’t have a job, you don’t appreciate what you actually have. And I think our folks really epitomize that. They really understand that jobs are delicate. They could go away. And so they appreciate the opportunities given to them.”

***

In contrast to Reyher’s division and its extension KES “Kennedy Employment Services”, McCrystal is the Vice President of Kennedy Industries, whose mission it is to create reciprocal partnerships that support the vision of persons with disabilities and their families and create opportunities for fulfilled lives.

McCrystal has been at the Kennedy Center for over 30 years, “I earned my Master’s in Art Therapy at Lesley University in Cambridge. When I was ready to look for a job, and based on the fact that there were only 15 schools in the country that offered art therapy as a major, you can appreciate how few jobs there were. But, at the age of 22, 23 that wasn’t my biggest concern. My biggest concern was doing what my heart wanted me to do. And so, the Kennedy Center and a company on Long Island miraculously both had a job opening for an Art Therapist. I was living in Rhode Island at the time. I came down here and I interviewed at the Kennedy Center but I also interviewed at the agency out on Long Island. Got offered both jobs in the same week, which is always sweet to have happened.”

McCrystal took that position at the Kennedy Center and there she has remained, bringing her insight and an artist’s sensitivity so her position, “You know, I think that artists can sometimes bring a different perspective to the table, and I think they are only one solution to our problem of supporting and propelling people with disabilities to their fullest. But, I think they’re an important component to have different perspectives at the table.

And so, over time we began using both artists and art therapists and dance therapists. And, augmenting the services and programs we were offering here. We did start the Calendar Project back about almost 30 years ago, and that certainly has been a great avenue for demonstrating the potential of people. (*See examples of the calendar artists on at the end of this feature.)

Over her tenure, McCrystal has spearheaded numerous programs within Kennedy Center including some of the central art therapy divisions, speaking to her sense of drive and optimism inherent to her character.

Of course, one cannot speak of the growth without visiting the hardships. “I would say that the biggest impact is certainly with our staffing,” McCrystal replied candidly, “I was just on the phone the other day with a mom who has a young 20-year-old who graduated from high school a couple years ago and really wants to come to the Kennedy Center, and he really needs one-to-one supports. And, I said to mom, ‘I can’t start your son until I hire staff.’

In our industry, the national average is a 30% turnover rate and we are unfortunately right about at that point right now. So much to do also with the salaries and the reimbursement rate. It has just been a 20-year struggle of trying to move that forward. As you know, the minimum wage has crept up in Connecticut, our starting rates for staff have stayed stagnant. So, we are a couple of dollars within that wage and these are jobs that are difficult, there’s a huge amount of responsibility; you’re caring for people’s lives and we’re barely paying our staff to start a job barely more than minimum wage.”

When you don’t have the amount of staff you wanted every day and you’re using on-call folks, you begin to pull away on things like those amazing community outings that you might do, because they do take more staffing. We’ve also, ironically, had to reduce some of our volunteer options that we were doing. We love to volunteer. We love to give back to our community. We love that message that people with intellectual disabilities can be as vibrant and as caring and as important in the local community as anybody else, and part of that is in saying we can give back and we can volunteer. But, again some of those volunteer options were fairly expensive to us. We might be delivering food. We might be delivering diapers. We might be putting 50, 60 miles on our vehicle to do that. Right now, we haven’t been able to do that because of how severe the budget concerns were for us.”

Despite the hardships the center faces every day, the same dedication to improving the lives of others I’ve found so bountifully in my conversations of the day, is found in McCrystal. “I rarely hear anybody say they love their job, and I can tell you I love my job. If you can embrace something and care about something, knowing that there may be no fanfare for it; there may be no big paychecks at the end of it, but that you know that you’re doing something that makes a difference . . . it is part of how you stay intact.”

As my day at the center draws to a close, I have a chance to sit down with the man at the beating heart of the Kennedy Center: President Martin D. Schwartz (who has since retired in early 2018). Schwartz served as president for nearly 39 years. With that kind of legacy, there is no better person than Schwartz to speak to the growth of the Kennedy Center from the grassroots organization to full-fledged national foundation.

Schwartz reflects back on the center’s humble beginnings, “Everything started with Evelyn Kennedy and a group of people that she got together in her kitchen. Evelyn was an amazing woman. As far as I know, I never really asked her, I think she had a high school diploma and I think that was it. You could have given her 20 PHDs she had such good judgment and knew how to present things.

It was wonderful to watch her. I’ve learned a lot from her. In a very, nice way she was able to accomplish anything that needed to be accomplished. Her reputation was well-established. Anytime there was a new governor they were instructed one of the first people that you need to talk to is Evelyn Kennedy.

When Jodi Rell was governor, she started this award called “Connecticut Treasure” where she would select certain people that she felt were invaluable to the state. The first one that she selected was Evelyn Kennedy.

Nationally, she was extremely effective in accomplishing a tremendous amount in terms of legislation. Certainly, on a statewide basis, she was instrumental in starting the Department of Mental Retardation, which became the Department of Developmental Services now. She was an incredible woman.

She started all this, in her kitchen over a cup of coffee by simply stating, “We need to do something.” In the beginning, they worked in the basement of a church and then it grew. I remember she would come to board meetings and we’d talk about the budget that continued to grow. She said, “Wow. I was going door to door with a cigar box to raise enough money for our programs. It’s just wonderful to see all of this happen.”

Her mission was a personal one. She had a child that was born in the mid-’40s. She saw that there were developmental delays, she went to the doctor, and the doctor said, ‘Put the child in an institution, forget that you had a child, and start your family over again.’ Her quote was, ‘I could never do that. I would never do that.’

Instead, she said, ‘My child is staying home and I’m going to find other parents that are keeping their sons and daughters at home and we’re going to do something here in the community.’ There was nothing at that time. Most people, when they heard the doctor said, ‘This is what you need to do . . . ’ they listened. Perhaps they lived to regret that at some point. Who knows? It was a very different time.”

Carrying on the dedication of Evelyn Kennedy, Schwartz is keenly aware of the family mentality at the heart of the center and that the entire organization started as a result of one mother’s unwillingness to abandon her child in need.

When asked about his own legacy Schwartz humbly answers, “Looking back 39 years ago, I knew I wanted to do this work. It just felt good. What are you going to do with your life? I want to make a difference. What else is there but to help other people? I felt that way. Looking back, I can’t imagine anything that I could have done that would have been as rewarding or as satisfying or fulfilling as running this organization. The people have been great. We have an amazing staff. The volunteers, the board of directors. We’ve grown a lot. We’ve diversified. I’m immensely proud.

What I hang my hat on is just the number of people, the thousands of people, that have come through these doors that have better lives as a result of it. That’s really where it’s at. The fact that we’ve diversified so that we’re able to serve so many more people who have different challenges but we’ve been able to help them to meet those challenges.”

***

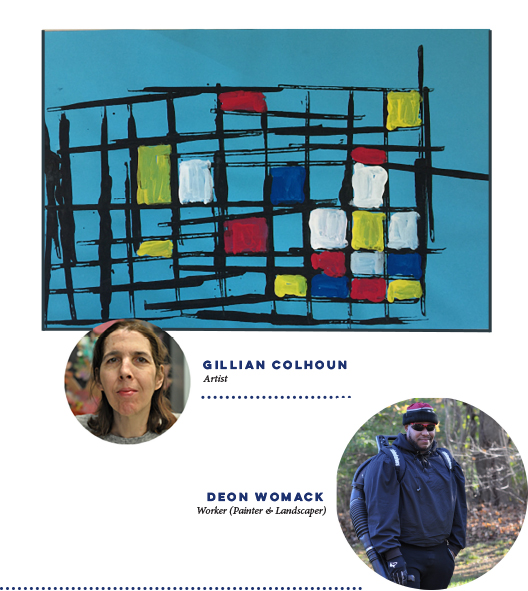

Beyond full-time care services, beyond job placement, and rehabilitation, The Kennedy Center is working to fulfill all the needs of their community both in body, mind, and spirit. A wonderful example of their endeavor to nourish the soul is The Maggie Daly Arts Cooperative or MDAC. MDAC is located in downtown Bridgeport, Connecticut. The cooperative is an exciting and unique initiative by The Kennedy Center designed to assist individuals with disabilities in creative exploration and self-discovery using: Visual Arts, Music, Dance, Yoga and more.

One of the most interesting aspects of MDAC is their “Artist First” philosophy, in which everyone who is in the program considers themselves to be an artist who also happens to have a disability. It is in approaches such as these that we see MDAC providing more than simply a means of expression but, rather, striving to provide its community with a conduit for self-definition beyond disability. Once again proving that they understand the needs of any individual go beyond the basics of survival and into the happiness found in body and mind.

***

In the end, with all their divisions and services, The Kennedy Center, like all organizations of its kind, is about the people they serve—a community of intelligent, capable, sensitive individuals who should never be underestimated.

In the end, with all their divisions and services, The Kennedy Center, like all organizations of its kind, is about the people they serve—a community of intelligent, capable, sensitive individuals who should never be underestimated.

The crisis in the Connecticut budget has since been resolved but funding is ever an issue. Schwartz retired in January and his successor, Richard Sebastian, is carrying The Kennedy Center into a whole new chapter.

During my time at The Kennedy Center, I met with the workers that endeavor tirelessly behind the scenes to keep this mission moving forward—the president, vice presidents, managers, behaviorists, therapists, nurses, case managers and direct care staff but, in the end, I truly met a group of impassioned employees working long hours on modest wages to protect and provide for one of the most vulnerable populations within our community.

In the individuals who attend Kennedy Center, I met workers, professionals, artists, mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers—I met those warm hearts who are no different than I and who deserve every opportunity that I will be given over the course of my life.

In the current climate, as marginalized communities face injustice and exclusion, I cannot help but remember the quote by Mahatma Gandhi, “The true measure of any society can be found in how it treats its most vulnerable members.” How to help organizations such as Kennedy Center in your community is as simple as volunteering or donating funds (however little you can spare). If you own a small business consider hiring an individual who suffers from a developmental disability in your business; you will be rewarded with a dedicated worker and a heart-filling experience.

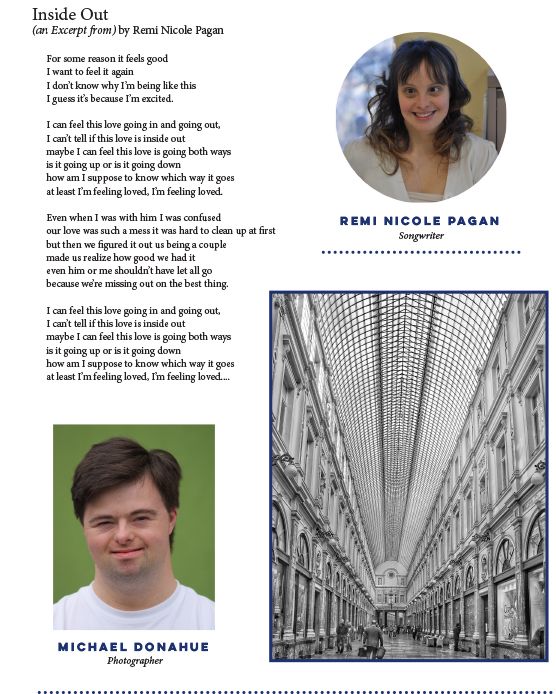

Faces of Kennedy Center

This is a selection from The Wayfarer’s spring 2018 issue.

Order the entire issue in either print or e-edition in our store.

The Wayfarer is a biannual magazine released in print and e-edition every spring and autumn. We publish a high-quality journal of literature and art that inspires and points the way for visionary-yet-practical change. By our definition, a “wayfarer” is a wanderer whose ability to re-imagine the possible provides the compass bearings for those on their way. The Wayfarer’s mission is to chart the way for change by building and empowering a community of contemplative voices. We seek to release a publication that builds and empowers a community of contemplative voices and serves as an agent for cultural transformation.

Subscribe to the Print Edition • Subscribe to the e-edition • Browse Featured Articles

L.M. Browning

Editor-in-Chief, The Wayfarer

L.M. Browning is a publisher, TEDx Talker, and award-winning author of eleven books. Balancing her passion for writing with her love of learning, Browning sits on the Board of Directors for the Independent Book Publishers’ Association, she is a graduate of the University of London, and a Fellow with the International League of Conservation Writers. She divides her time between her home along Connecticut’s shore and Boston where she is earning an L.B.A. in Creative Writing and Journalism at Harvard University’s Extension School. Look for Leslie’s next book, To Lose the Madness: Field Notes on Trauma, Loss and Radical Authenticity. Visit her at www.lmbrowning.com

Kelly Kancyr

Editor At Large, The Wayfarer

At the rebellious age of 8, Kelly Kancyr turned her first instrument—the violin—(her mother’s choice) into a guitar, playing it like a distorted Les Paul. Learning in that moment that musical instruments don’t have to be played in a traditional way; a philosophy that lies at the heart of her style. Drawn to wide array of genres, Kelly finds she can change musical stylings as easily as she has moved around the world. Johnny Cash, Joni Mitchell and Lucinda Williams, are just some of the influences echoing as undercurrents to her songs. In her vintage folk rhythms and emotionally raw lyrics, you can hear both the wide open spaces of Santa Fe, and the rocky beaches of the east coast. Now 20 years into her career, Kancyr finds herself taking on the role of a mentor and producer. Kelly has performed throughout the United States. Her music has been featured on television stations such as ABC-WTNH, and radio stations such as WNHU and WPKN. She is a graduate of Quinnipiac College. She joined the The Wayfarer staff in 2018 and has helped to spearhead the audio division of Homebound Publications. She is Co-Founder and Producer of The Vanguard Podcast (Homebound Publications’ seasonal podcast exploring the forefront of creativity).

To bring each issue of The Wayfarer to fruition, it takes hundreds of hours each season to craft, edit, design, and distribute the journal. If you find joy and enrichment within our features, please consider becoming a supporter with a small donation. There is no set amount. Whether it is .99 or a few dollars, we appreciate any gift you care to give. While at this time we are not a non-profit all donations do go towards ensuring the future of the journal.

Help us Empower Change by Giving a Little Change!